In “Blood-Burning Moon,” Toomer avoids prejudice, assumptions, and labels, as a third person narrator. While the characters do make some assumptions about one another, Toomer, as the narrator, refuses “to endorse this racial divide” in his narrative (Sollors 367).

When beginning his narrative, Toomer immediately establishes the characters by their specific names rather than derogatory language or labels. Although the word “Nigger” is used few times, that was common at that time. People of color frequently called each other by this name: “Shut up, nigger. Y dont know what y talkin bout” (Toomer 45). Thus, when Toomer uses this term, it is not to demonstrate prejudice. His dialectic choice was following the language norms of the time. Moreover, Toomer uses “nigger” to refer to black people in general, and not just Tom Burwell or Louisa. His ambivalence is also seen through the names Bob, Louisa, and Tom, which are all common names and do not have a visual racial origin. Some characters, however, use the term “nigger” in a racist way, such as the mob at the end of the story. For instance, when the mob says, “Hands behind y, nigger” (48), I believe the character is being racist because he does not need to say “nigger” at the end of his sentence. It is included as a derogatory insult to show his superiority to Tom Burwell.

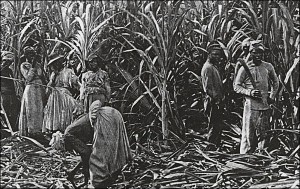

Toomer avoids assumptions about race in the choice of his plot. In the conventional stories displaying African-American life, black people go with black people, or, if there is a interracial relationship, the white man will be the dominant one. Toomer’s short story diverges from this cliché and presents a story where race is irrelevant, at least, from the narrator’s point of view. Louisa, the African-American heroine, has difficulty choosing between the two men who are in love with her. Tom Burwell, who is also an African-American man, works in the cane plantation and desires Louisa’s love and hand in marriage. He has a hard time expressing his feelings, especially as he cannot spend much time with her because of his work: “but working in the field all day, and far away from her gave him no chance to show it” (39). Conversely, there is Bob Stone who is the son of the planter who employs Louisa. He is interested in Louisa solely due to the sexual aspect of their relationship. Despite racial differences, Bob Stone continues to pursue Louisa and her affections for him grow, “by measure of that warm glow which came into her mind at thought of him, he had won her” (39). She likes him more because she spends more time with him, not because he is white. At least, the narrator never utters it.

In the story, there is no indication of discrimination. The two men are fighting for Louisa’s heart–a common plot. Louisa is the one who has the power, which is highlighted by her passivity to not make a choice. She is undecided and enjoys being desired by both men. When Tom cuts Bob’s throat as they fight for her love, Toomer depicts a black man winning over a white man and thus gaining equality. Although the scene is very violent, Toomer demonstrates that race does not indicate superiority, black men can be powerful as well. Moreover, Tom does not kill Bob because of race, but because he is jealous. Tom’s reputation for violence is independent of race and Toomer illustrates this when Tom tells Louisa, “Ise already cut two niggers” (43). They hate each other not because of their color of skin but because they love the same girl and therefore are jealous of each other.

Toomer avoids prejudice in Cane’s story because he spends as much time talking about Tom as talking about Bob or Louisa. In this story, there is no reference to skin color. This story is about two men in love with the same girl and thus fighting for her. Although there is prejudice present within the story, it is not Toomer’s prejudice.

Works cited:

Toomer, Jean. “Bood-Burning Moon.” Cane. New York: Livericht, 2010. 39-49. Print.

Sollors, Werner. “Jean Toomer’s Cane: Modernism and Race in Interwar America.” Cane. New York: Norton Critical Edition, 2010. 357-376. Print.

Leave a Reply