12 May, 2020

I didn’t want it to end like this.

Here I was, sequestered in my study, staring into my laptop screen in hopes that most of my similarly isolated students, nearing the end of their first college year, would have the computer equipment and bandwidth necessary to participate in our first Zoom-enabled class meeting since the college moved all instruction online in mid-March.

For the previous ten weeks, we 16 had gathered together in a small seminar-style room near Atlanta to study graphic memoirs, engaging in lively discussions of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, an exhaustive (and sometimes exhausting) exploration of the history, vocabulary, and formal aspects of what his subtitle calls “the invisible art.” My students and I were anything but invisible to one another; in fact, much of the intellectual excitement had occurred because of our physical proximity, with our expressions, gestures, verbal exchanges, and occasional cross-talk all contributing to the palpable excitement I felt during every class session–and I sense most of my students shared.

My feelings about this particular class were also mixed with wistfulness, since this was the last I would teach in a 40+-year career.

And now, on our first day in a virtual classroom, both feelings vied with anxiety as I opened what the Zoom programmers have labeled the “waiting room” (block that metaphor!) to admit my awaiting students. While most managed to tune in, many kept their video turned off, and the few who ventured to speak in this all-digital environment often sounded as if their voices were passing through a filter designed for informants or whistleblowers determined to conceal their identities. Their reticence made me wonder if many looked on these meetings as the equivalent of a necessary but dreaded visit to the doctor.

As Kate Murphy wrote in her 29 April New York Times piece “Why Zoom is Terrible,” video chatting is fine “for letting toddlers blow kisses to their grandparents,” but when it comes to the exquisitely complex and tactile in-person communication of adults, video conferencing technology is a blunt and blunting instrument. Explaining the concept of “mirroring,” Murphy says we all “engage in facial mimicry whenever we encounter another person,” which she calls “a constant, almost synchronous, interplay” that involves physically embodying the other person’s non-verbal cues, her emotional “temperature.” This “makes mirroring essential to empathy and connection,” Murphy notes. No high-tech screens, speakers or mini-cams can reproduce this kind of engagement.

Imagining the next two months inside this simulacrum of a classroom, I was moved to ask with Robert Frost’s oven bird “what to make of a diminished thing.”

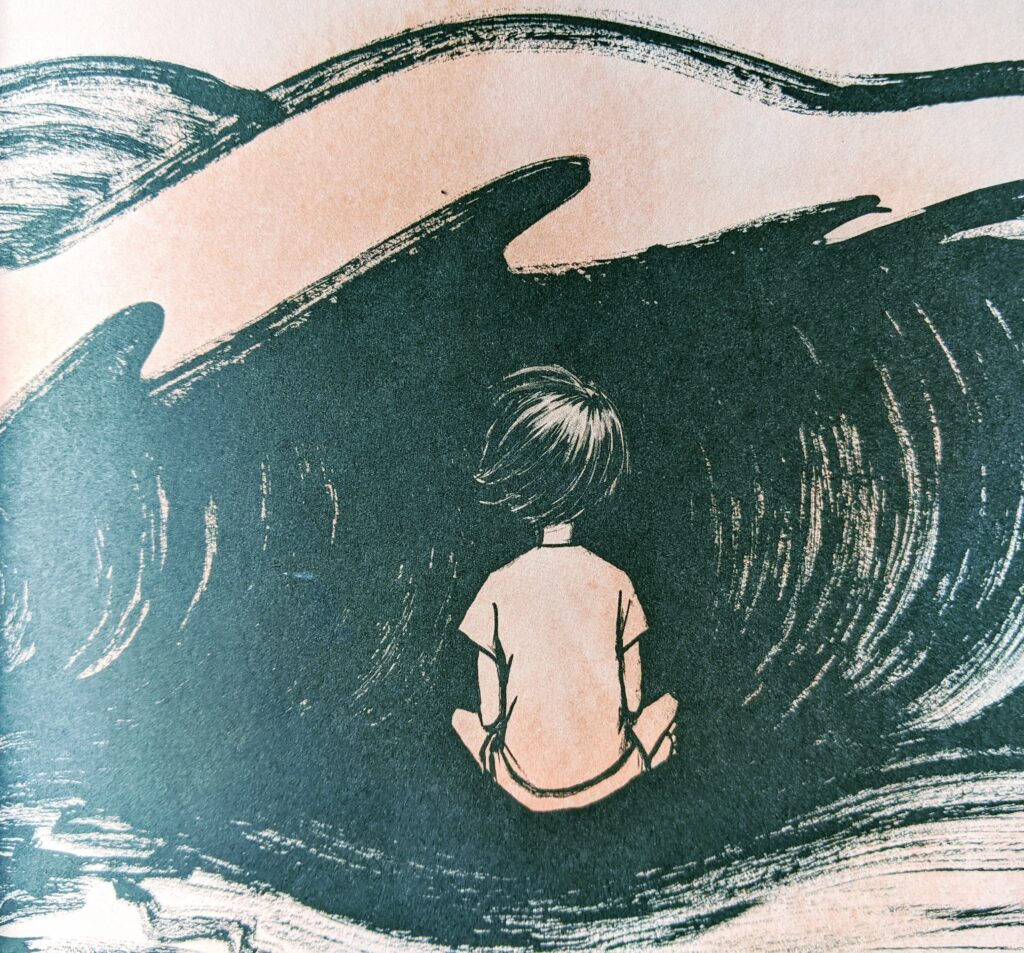

I took solace in the fact that for the remainder of this compromised semester we would be discussing The Best We Could Do, Thi Bui’s beautiful, harrowing memoir of her family’s immigration from Vietnam to the United States in 1978, and of her desire to understand and help break the cycle of trauma that haunted and troubled her parents’ lives. When I initially added this book to the reading list for my Spring 2020 course, I had no idea the added resonance it would take on as the COVID-19 pandemic forced all of us inside. When we began discussing chapter 4 of Bui’s memoir (whose title I have borrowed for this essay), my students and I experienced an unsettling shock of recognition.

“Home, the holding pen.” This is how Bui describes the cramped concrete apartment in San Diego where she and her family lived during her childhood. My students, all of whom had reluctantly returned to their family homes in March after enjoying most of their first year living independently, readily identified with the feeling of “claustrophobic darkness” she experienced during this period. And many in our ethnically and geographically diverse class also understood too well the metaphorical implications of Bui’s suggestive phrase: the twin viruses of xenophobia and racism that Thi and her parents experienced whenever they ventured out in public.

Several of my students also noted that Bui’s use of the phrase “holding pen” has a special relevance at this time in our country’s history, and one student shared an article from her hometown newspaper describing the literal holding pens that U.S. Border officials have constructed in places like El Paso to confine Central American families who crossed into the country seeking political asylum. If we had been able to meet in person while discussing this book, whose every page reminds us that the personal is the political, my students would have been able to more freely and fully share their own truths of this axiom.

* * * * *

My brief experience of “distance education” has brought into sharper focus for me what is precious, and irreplaceable, about face to face liberal arts education, whether conducted in seminar-style classrooms at large public universities or small residential colleges—and what the economic impact of the pandemic is threatening as never before. I began my career at the University of Washington, where I taught 20 or so students each quarter in the Freshman English program, and went on to teach at Chapman College (now University) in southern California; Albion College in Michigan; the Newberry Library in Chicago (which hosts co-taught, interdisciplinary seminars for juniors and seniors each year); and Agnes Scott College in Atlanta, which has been my academic home for the past 15 years. In each of these settings, my favorite moments have occurred when ideas, through (subtly, I trust) orchestrated classroom conversation, are clarified, sharpened, become important to students—in and beyond the classroom.

In his wonderful essay “On the Education of Children,” the philosopher Michel de Montaigne describes the capacity of such conversation to “rub and polish our brains by contact with those of others.” Notice the tactile nature of his metaphor. Often the most important thoughts in a given class I conducted have been embodied—communicated through gestures, facial expressions, eyes that convey surprise at a new discovery, opposition to the claim of a fellow student, righteous anger at an historical or current injustice represented in a literary or historical text under discussion. And I remember the countless times and ways I used gestural as well as verbal means of expressing encouragement, eliciting interpretive risk-taking, seeking greater clarity and specificity from my students. Most of this is lost in the pixelated world of online instruction.

Other losses during the lockdown include all of the out of the classroom experiences that enrich the lives of student and faculty: chance encounters and exchanges on the college quad; office hour conferences; informal discussions with students and colleagues in the dining hall; field trips to visit people, sites, institutions shaped by the ideological forces that our various disciplinary tools are designed to better understand, and question.

And herein hangs a tale to illustrate what I have missed most about teaching in these plague months.

In the fall of 2017 I taught a section of a course required of all first-year students at Agnes Scott: a leadership seminar designed to improve students’ critical thinking skills and ability to work with others in identifying and addressing contemporary challenges. All sections of this course are designed to support the college mission: educating women “to think deeply, live honorably, and engage the intellectual and social challenges of their times.” When I originally designed the course back in June, I intended to focus on “International Atlanta,” and combine field trips with reading and research focusing on a variety of leaders–in the fields of politics, medicine, economics, and social justice. But two weeks before classes began, a counter-protestor was killed during a white supremacist protest in Charlottesville, organized to oppose the planned removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee astride his horse.

Given the central role Atlanta played in the Civil Rights movement, and the persistence of racist violence in America, I determined to narrow my scope. I had already planned to use John Lewis’s graphic memoir March: Book One, about his formative years as a Civil Rights leader, but I added E.L. Doctorow’s novel The March to the reading list (about Sherman’s defeat of the Confederacy in the south), as well as Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens’ infamous 21 March 1861 “Cornerstone” Speech (“our new government is founded upon . . . the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition”). I shifted my focus to the legacy of the Civil War, Jim Crow, and the Confederacy.

In May, I had joined Agnes Scott’s Director of German Studies and seven other colleagues on a study trip to East Germany. All of us were struck by the myriad ways in which the German government had contributed to that country’s Vergangenheitsbewältigung (“confronting its past”)—not only by banning any public displays of Nazi symbolism but by supporting memorials, museums and initiatives that document what Professor Randy Malamud has called the “meticulously evil” methods of the Third Reich. We were equally struck by the comparative failure of the United States to come to terms with its own meticulously evil system of slavery, racial apartheid, and the white supremacist ideology that has enabled it.

I knew that in front of Agnes Scott’s Main Hall, constructed in 1891, was a prominent stone monument honoring a Confederate regiment for a fleeting 1864 victory over a Union regiment during the Battle of Atlanta. I also knew that the city square in nearby Decatur had a monumental obelisk honoring the “lost cause” of the Confederacy (constructed in 1908, two years after the Atlanta race riot, as a symbol of white supremacy designed to intimidate African-Americans). So I decided that our class would undertake research, field trips, and team projects about Confederate ideology and symbolism, beginning with the founding documents of the Confederate States and including contemporary campaigns to remove Confederate memorials and other symbols (including a 1992 protest against the Georgia State flag organized by a group of Spelman students that included Stacey Abrams).

So as not to try my readers’ patience, I will try to summarize the results of my course correction briefly. After several weeks of reading narratives and historical documents about the Civil War, the Confederacy, and the emergence of the “Lost Cause” ideology (the role of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in this false religion troubled my students more than anything), we took a series of field trips to related sites—the The Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park; the The National Center for Civil and Human Rights; the front entrance to the college, where the Confederate memorial rested beneath towering oak trees; the Decatur City Square, whose towering monument reads in part that the Pro-Slavery Confederates “were of a covenant keeping race who held fast to the faith as it was given by the fathers of the Republic.” While opinions among my students about what to do with the monuments we visited varied, the question I remember most vividly from our last field trip was this one: “why are the traitors the ones who get honored?”

During the second half of the semester, I divided the class into four teams, and asked each team to develop, research, and present ideas for changing something about these memorials—or defend their continued existence. Their final presentations to the class included proposals to commission a statue honoring John Lewis, who represents the 5th Congressional District that includes Decatur, to stand beside the Decatur obelisk; to topple the obelisk, and leave the resulting rubble to symbolize the destruction of white supremacist ideology (this team created a Styrofoam model of the resulting display); to redesign the Georgia State Flag so that it no longer includes Confederate symbolism; and to remove the Confederate memorial on the college campus. One year after this last proposal, and as a result in part of another course on local Confederate monuments taught by my colleagues Katherine Smith (in Visual Arts) and Robin Morris (in history), the memorial was removed from the Agnes Scott campus.

The team seeking to change the state flag gave a particularly effective proposal. First they illustrated the remarkable similarities between the first national flag of the Confederate States and the current Georgia State flag, approved in 2004 after years of controversy:

After reminding the class of the many ways in which post-Civil War Confederate ideology influenced everything from Jim Crow laws to history textbooks to contemporary white supremacist ideas and symbols, team members showed a video of the Charlottesville white nationalists brandishing Confederate battle flags while chanting “Jews shall not replace us.” They ended by presenting their design for a new Georgia state flag, distributing small paper versions attached to small wooden “poles” to each member of the class:

This is the kind of active, engaged learning that happens best in social settings, when we are present to and for one another, able to “rub and polish our brains by contact with those of others.” It is missing in this time of physical distancing, and distance learning, and I will miss all the many inspiriting instances of it I experienced in a privileged career.

In How to Think Like Shakespeare, which I recommend to everyone who cares about the art and discipline of good teaching, good thinking, and good writing, my former student (now Rhodes College professor) Scott Newstok tells us that his book offers “not only an exploration of thinking, but an enactment of it, for ‘joy’s soul lies in the doing’” (the last six words are Shakespeare’s, from Troilus and Cressida). In his chapter “Of Thinking,” Newstok relates a telling anecdote, which provides an appropriate note on which to end this valedictory essay, dedicated to my students and colleagues, past and present. “According to the dancer Martha Graham, when Helen Keller placed her hands on the great American dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham to feel him leap, she marveled: ‘how like thought. How like the mind it is.’”